Everything is in constant change, particularly the external environment of the companies which is constantly and rapidly changing. Understand and predicting change is difficult and sometimes almost impossible. So, how do we have an effective change management? Nevertheless, being able to manage change is key.

Check out the first blog post in this series.

Industry/product life cycle

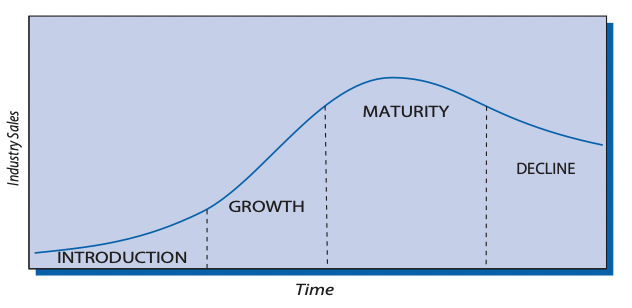

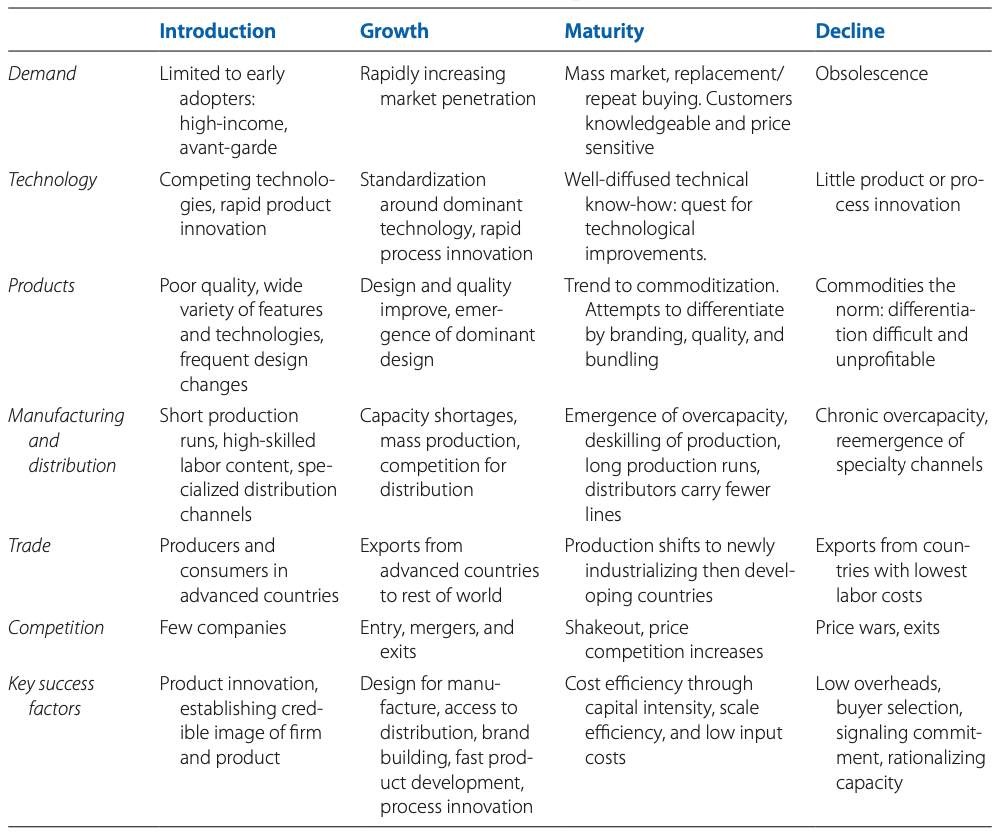

As you recall from the corporate strategies section, the product life cycle is linked with the growth rate and sales and is key to decide when there is a need to redefine strategy. As products have life cycles, the same logic can be applied to the industry that produces them. Industries produce different generations of the same product and have longer life cycles (i.e.: the smartphones industry produces different models of smartphones). The industry life cycle has 3 stages concerning sales:

- Introduction stage: sales are low because the product is being introduced and is still unknown. Costumers are still scarce as the producers.

- Growth stage: market penetration accelerates and production improves. The product becomes mass-market.

- Maturity stage: the maturity is reached and the demand starts to decline and search for new offers.

- Decline: the product is challenged and replaced by new options and the demand starts to decline sharply.

Furthermore, the industry life cycle is also affected by knowledge and not only demand. Knowledge in the form of innovation is responsible for the appearance of a new product. The first stage is characterized by fierce competition between different product options (if available) and it then converges to a dominant design and technical standard. When the industry gets into the growth phase, the product becomes standard and the focus of the company is in process innovation and production capacity in order to reduce costs.

Obviously, not all industries have the same life cycles. For example, the hotel industry has a very low life cycle as the MP3 players industry had a very rapid life cycle which came from introduction to decline in very few years.

Adaptation for Effective Change Management

Organisational inertia

Based on what we saw, we conclude that change is inevitable as proved by the industry life cycle. Companies must also change and adapt but most of the times, this is hard to achieve. The first reason is organizational inertia which is the tendency to continue operating exactly the same way regardless of the change. This is due to the following:

- Organizational routines: mature organizations get very established routines. As more established they are the more difficult it is to change them. It is possible that core capabilities become core rigidities (competency traps).

- Social and political structures: the structure of the company which was developed along time, can be a blocking point to change. This is due to very established positions and ways to perform activities. Change threatens the ones in power positions (i.e.: long term employee or manager).

- Conformity: organizations tend to imitate one another and function in the same way. Becoming so homogeneous in this sense makes change difficult.

- Limited search: companies tend to perform research in areas close to the ones already known [exploitation] and tend to avoid the unknown and uncertain [exploration] which blocks them to foresee new opportunities.

Regardless of organizational inertia, the industry will change and the companies that are able to remain in business will need to adapt. Otherwise, they will be replaced by new companies or loose market share to the ones that were able to have a coherent change management strategy. Organizations that are able to change will adapt their organizational routine: unsuccessful routines are abandoned; successful routines are retained and replicated within the organization. Companies can combat inertia as follows:

- Creating perceptions of crisis: when a crisis hits a company it may be to late to change and survive. An alternative is to create a constant perception of crisis inside the company. This perception will help change to occur.

- Establishing stretch targets: companies can fight inertia by establishing challenging targets and objectives to individuals and business units. This objectives must the achievable (SMART objectives) but at the same time challenging. With challenging objectives comes innovation.

- Organizational Initiatives: create regular activities which alert for the need to change and innovate.

- Reorganize the structure: reorganizing the structure of the company allows changes in established positions which could foster innovation as new people enter the organization or change places within it. New leaders might be needed to reduce inertia.

- Scenario analysis: adapting to change requires anticipation. Scenario analysis is a way of thinking about how the future will be and analyze possible industry outcomes. Scenario analysis is a powerful tool for communicating different ideas and insights, identifying possible threats and opportunities, generating and evaluating alternative strategies, and encouraging more flexible thinking. The analysis also allows the evaluation of different strategies under different scenarios and understand which would be the best.

Change management when Dealing with technological change

The development of new technologies is the main threat to stability but also essential to overall progress. Nevertheless, technology will affect companies and it is mainly brought by new firms which offer different solutions. Technology can be particularly challenging if it is:

- Competence destroying: technology affects the resources and capabilities of a company. When technology is competence enhancing it can improve the resources and capabilities of the firms (e.g.: a new technology that improves the final product of an established firm). On the other hand, technology can be competence destroying if it affects the resources and capabilities if the firm (e.g.: a new technology that makes a product obsolete as smartphones made to MP3 players).

- Architectural: technology is architectural when it changes the overall architecture of a product and it will require major adaptation from the firm side (i.e.: the product will need to be radically changed to adapt to the technology). Technology can also be component if it does not require the total adaptation of the product. An example is the hybrid plug-in engine which is a slight adaptation of vehicles and the completely electric vehicle which requires the total adaptation of the product.

- Disruptive: sustaining technology improves the existing performance of products but disruptive technology bring completely new performance and attributes. This will cause also disruption in the industry. An example can be digital photography which was disruptive regarding the existent technology. It also led to developments in other industries as incorporation of cameras in cell phones or cars.

Managing strategic change management

In order to deal with change, organizations might pursue different strategies which are explored below.

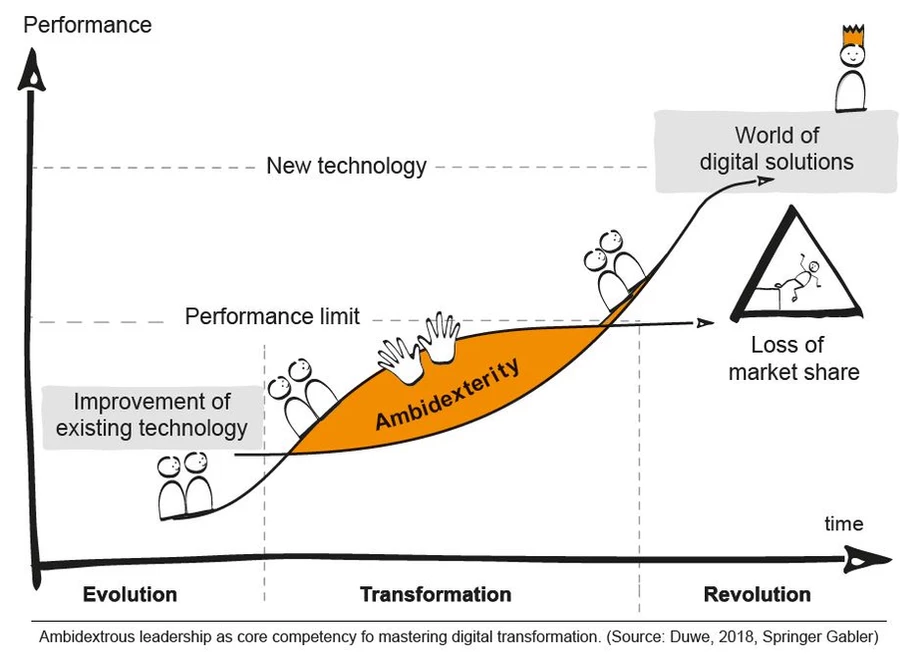

Organizational ambidexterity

Organizational ambidexterity is closely related with the idea of “competing for today” with “preparing for tomorrow” is closely related the idea of research in organizational inertia (i.e.: companies tend to research areas close to the ones that they know [exploitation] already than to explore new opportunities [exploration].

Structural ambidexterity happens when a company decides to pursue exploration and exploitation in different locations. This will improve the innovation process (e.g.: IBM developed its PC unit far from its headquarters to create a radically different product). On the contrary, companies might pursue a contextual ambidexterity which is the opposite concept of structural ambidexterity. In this case the same organizational units and the same organizational members pursue both exploratory and exploitative activities. The employees are encouraged to sustain existing products while pursuing innovation and creativity. The strategy to follow depends on the company and on the type of product and innovation required. If a radical/disruptive innovation is required, structural ambidexterity would be preferable while an incremental innovation would be better pursued with contextual ambidexterity.

Developing new capabilities

In order to obtain a competitive advantage, there is the need to develop capabilities. Distinctive capabilities are likely to be found in the early days of a company that then evolved along years of history. Therefore, capabilities are subject to path dependency as they are the result of companies’ history and are established along many years. As we have seen in organizational, companies must be careful with their structure because as deeply established the capabilities are, the harder it is to develop new ones and adapt to change.

Developing new capabilities always requires processes (i.e.: organizational routines that allow a task to be performed efficiently, in a repeated and reliable way), structure (i.e.: organizational structure needs to be aligned with capabilities as the capability to develop needs to be within the same organizational unit), motivation (i.e.: motivate the team to achieve the objectives) and alignment (i.e.: the development of a capability must be aligned with the entire organization or organizational unit. From the smallest to the most important task, that capability must be incorporated in the daily jobs). Capabilities will be developed sequentially and along time (not at once), integrating the 4 concepts mentioned before.

Dynamic capabilities

As we have seen before, dynamic capabilities concern the “firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” (Grant, 2018). By sensing opportunities and seizing them and transforming the organisation, it is possible to achieve change management with results as the company will always be attentive to market changes. However, dynamic capabilities suppose their identification in a specific process. For example, a company must identify several processes and fund them to find new business opportunities.

Gary Hamel challenges the vision that a dynamic capability can be built on a process or routine as the author believes in constant radical change. He states that “the company that is evolving slowly is already on its way to extinction” (Grant, 2018). The idea is that companies that thrive are constantly innovating and adapting at the same time that are socially responsible. The author believes that the current system of thinking must be changed in order to create economic growth.

HBS: change management process

As we have seen, change is inevitable and organizations must be ready to deal with it. According to Harvard Business School (HBS) organizational change “refers broadly to the actions a business takes to change or adjust a significant component of its organization. This may include company culture, internal processes, underlying technology or infrastructure, corporate hierarchy, or another critical aspect”. Changes might be adaptive (i.e.: small and gradual) or transformational (i.e.: large scale and sudden which will cause disruption in the company).

HBS developed a change management process that helps to guide organizations to fruitful change once it arives. The process has the following steps:

- Prepare the organization for change: managers should raise employees attention to the need for change. This initial engagement of employees will help implement change and reduce friction later.

- Craft a vision and plan for change: managers should now create a plan to implement change. The plan should include:

- Strategic goals: what we will achieve with the change;

- Key performance indicators: measure the success of change;

- Project stakeholders and team: people that will oversee the implementation of change;

- Project scope: the steps that the project includes and what falls outside the project scope.

- Implement of change management: follows the plan that has been developed earlier that could include changes to the company’s structure, strategy, systems, processes and employee behaviors. It is crucial to engage employees at this step and repeat the communication about the need for a change.

- Embed changes within company culture and practices: guarantee that the change is not reversed as without an adequate plan the employees might to go back to previous habits. Embedding changes within the company’s culture and practices will help to sustain the changes made.

- Review progress and analyze results: the project’s conclusion does not mean that it was successful. Either way, the results must be analyzed at the end and take conclusions. Either a successful or unsuccessful project creates valuable insights into the future and will help the organization to not repeat the same errors or follow a successful path (remember that capabilities have a path dependency). A case study should be created with the lessons learned.

TED Talk: 5 ways to lead change management in an era of constant change

In this TED Talk, Jim Hemerling builds on the idea that change is constant and sudden. He argues that leaders are mostly acting in a crisis mode which will only react once the change is already happening. This will only try to survive the change and sometimes it can be too late. The argument is that organizations can only thrive if they put people first (similar to Gary Hamel). However, the speaker argues that transformation can be gradual and not exhausting if organizations take it as a continuous process.

The speaker provides 5 ways to help organizations lead in times of constant change putting people first: (1) Inspire through purpose: have a meaning vision and mission; (2) Go all in: not think only about the financials but actions that drive growth in the future; (3) Enable people with the capabilities: empower people with the capabilities to succeed during and after the transformation; (4) Gradually create a culture of continuous learning: change from a culture of competition between employees to a culture of growth where organizations are capable of taking the best out of employees; (5) Inclusive leadership: include people in the decisions and make people comfortable to contribute.

Resources and References

Main

- Barney, J. & Hesterley S. (2019). Strategic Management and Competitive Advantage: Concepts and Cases. 6th Edition, Pearson.

- Grant, R. (2018). Contemporary Strategy Analysis. 10th Edition. Wiley.

Secondary

- Adam Brandenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff, Co-opetition (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1996)

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management.

- Bredrup, H. (1995). Competitiveness and Competitive Advantage. In: Rolstadås, A. (eds) Performance Management. Springer, Dordrecht.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1212-3_3

- Boddy, D. (2020). Management: Using Practice and Theory to Develop Skill (8 ed.). Reino Unido: Pearson.

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Sage. (direct link)

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look. Int J Corporate Soc Responsibility 1, 3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6

- Casadesus-Masanell, R. (2014). Introduction to Strategy. Harvards Business Publishing

- Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T., & Eisner, A. B. (2010). Strategic management: Text and cases. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Lacaze, A., & Ferreira, F. (2020). Adding Value to the VRIO Framework using DEMATEL. Lisbon: ISCTE-IUL. (direct link)

- Levitt, T. (1958). The dangers of social responsibility (pp. 41–50). Harvard business review

- Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2004). Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business Review. (direct link)

- Miller, D. (1992), “The Generic Strategy Trap”, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 37-41.https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039467

- Nagel, C. (2016). Behavioural strategy and deep foundations of dynamic capabilities – Using psychodynamic concepts to better deal with uncertainty and paradoxical choices in strategic management. Global Economics and Management Review, 44-64. (direct link)

- Pearce, J. and Robinson, R. (2009), Strategic Management – Formulation, Implementation and Control, 11th edition, McGraw-hill International Editions

- Porter, M. E. (1979). How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review. (direct link)

- Porter, M. E. (1985). The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. NY: Free Press

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press.

- Porter, M.E., & Kramer, M.R. (2011) ‘Creating shared value’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 89, no. 1/2, pp. 62–77.

- Sharda, R., Delen, D., & Turban, E. (2018). BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE, ANALYTICS, AND DATA SCIENCE: A Managerial Perspective. Pearson.

- Teece, D. J. (2011). Dynamic capabilities: A guide for managers. Ivey Business Journal. (direct link)

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1998). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal. (direct link)

- Treacy, M., & Wiersema, F. (1993). Customer Intimacy and Other Value Disciplines. Harvard Business Review. (direct link)

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). The Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal.

Websites

- https://ebrary.net/99185/business_finance/which_prioritie

- https://managementweekly.org/porters-generic-competitive-strategies/

- https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/bezos-is-coming-mapping-amazons-growing-reach

- https://www.business-to-you.com/ansoff-matrix-grow-business/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/levels-of-strategy-corporate-business-functional/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/porter-generic-strategies-differentiation-cost-leadership-focus/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/value-disciplines-customer-intimacy/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/vrio-from-firm-resources-to-competitive-advantage/

- https://businessjargons.com/internal-environment.html

- https://www.finereport.com/en/data-visualization/a-beginners-guide-to-business-dashboards.html

- https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/change-management-process