The external environment is composed by forces outside the firm and outside its control. These forces also influence the firm and can be sources of market opportunities as well as competitive advantages. At this stage it important to distinguish between industry and market: “the term industry tends to refer to a fairly broad sector, whereas a market refers to the buyers and sellers of a specific product” (Grant, 2018). Therefore, the packaging industry comprises several markets such as steel cans, aluminum cans, paper cartons, and many others.

Environment analysis

The profitability of the companies may largely depend on the industry in which they are operating. Therefore, a company might be more likely to be profitable if it operates in a specific industry. For instance, large pharmaceuticals are generally more profitable than large telecommunication companies. However, the profitability of a given industry cannot be simply explained by supply and demand curves based on the assumption of the existence of undifferentiated products offered by competitor companies. A company might itself influence the price of a product simply because it offers a higher quality solution which costumer are willing to pay for.

In 1979, Michael Porter proposed a framework to analyze structural factors, focusing on how they influence industry profitability. Its power lies in its incorporation of the real-world, commonsense variables, or forces, that can make a particular industry an easy or difficult environment. This is a tool more dedicated to the corporate strategy but which directly influences business strategy as the following chapter will explore.

Originally, the framework was composed of 5 forces influencing companies’ profitability and later a further force was included (opportunity of complements) by Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1996:

- Threat of new entrants: new entrants in a market erode profitability as incumbents will lose market share. Usually, it is easier for new companies to participate in a low regulation market, without economies of scale or strong brand identity. For instance, it is easier to enter in the market of Android application than pharmaceuticals.

- Bargaining power of the suppliers: if the suppliers offer an unique product or are very specialized and just a few, they will have a high bargaining power and can increase prices. For example, Coca-Cola offers a unique product, and its buyers (retailers) are dependent on the price charged.

- Bargaining power of the buyers: the power of the costumer also has an impact on companies’ profitability. If there are just a few buyers their power increases. For instance, big retail chains (Walmart, Continente or Pingo Doce) have a high bargaining power and the industries that sell through them are dependent on the prices that large retailers wish to buy.

- Industry competition: competition is normal in a free market but if it is too intense in a particular industry, it will erode companies’ profits. Intense rivalry is common when the competitors are of similar size and sell undifferentiated products, or when industry growth is slow.

- Complements/substitute products: substitute products are the ones who perform mostly the function and can be easily substitutable. For instance, it is easy to replace an Android application for a similar one which performs the same function.

- Opportunity of complements: A firm has a complement when its goods are made more valuable by those of another firm. Businesses can create significant value when they complement one another, even while competing to claim that value. Consider the history of Microsoft and Intel. In the early years of the personal computer (PC) industry, Microsoft’s Window operating systems could work only with Intel processors. Jointly, the companies exercised considerable power over the market, and their success was closely linked.

You can explore the different interactions between the forces using the following tool:

Adapted and reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. Exhibit from “The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy” by Michael E. Porter, January 2008. Copyright© 2008 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.

Grant, 2018 argues that there is a missing force in Porter’s model, namely, complements. Porter argues that the existence of substitute products reduce the industry profitability as consumers can choose among several options which, without differentiation, will increase price wars among the companies. However, the model neglects the existence of complementary products to the ones the company is offering. In this case, complements have a positive effect increasing the industry’s profitability.

- Nintendo: in the 1990s Nintendo was a great success and the company kept proprietary dominance over its operating system. Most of the revenue and consumer value was in the games created by independent developers but Nintendo got most of the profit as it dominated the games manufacturers and besides the operating system control, the company also control the production of games cartridges.

- Apple: the company has total control of its iOS operating system. Therefore, it controls which apps are offered in the Apple Store which allows the company to get 30% of the revenues that these apps generate.

The existence of complements creates an externality as a company profits from complements and complements profit from a company which products/services have the most consumers. Take the example of Android which has millions of different apps which are developed as complements due to the large number of Android users. This creates profit potential for both parties.

The airline industry

The airline industry is most of the times considered a fancy business but, in fact, is not a profitable industry. This is due to the fact that airline companies operate in an extremelly competitive environment subject to different shocks such as fuel prices, regulations and recently a pandemic. There are many operating companies in the airline market which creates the rivalry among firms very high. The threat of new entrants is medium as this industry has high fixed costs and high exit barriers. It also requires a considerable sum to start a business but there is no need to buy planes as they can be rented. The brand images also plays an important role here. The bargaining power of suppliers is very high as there is not much providers of airplanes, airplane fuel or highly specialized human capital. The bargaining power of buyers is also very high due to the existence of other airline companies which can serve as alternatives. The threat from substitute products is medium as consumers can chose other options for transportation such as car or train. However, for long distances these options might not be feasible. Concerning complements, we can say that there are not many complements available for the airline industry. Examples of complements might be: airplane food, entertainment on board of services provided onboard.

Business strategies

After a certain industry has been selected according to its expected profitability and using the framework already explored, a company might adopt one of the two available generic strategies, namely, cost leadership or product differentiation.

Analysis

We will now analyze the main cost drivers and the sources of uniqueness.

Cost drivers

- Economies of scale: technical input-output relationships, indivisibilities, specialization,

- Economies of learning: increased individual skills, improved organizational routines,

- Production techniques: process innovation, re-engineering of business processes,

- Product design: standardization of design and components, design for manufacture,

- Input costs: location advantages, ownership of low-cost inputs, labor, bargaining power,

- Capacity utilization: ratio of fixed to variable costs, fast and flexible capacity adjustment,

- Residual efficiency: resources available, motivation and organizational culture, managerial effectiveness.

Sources of uniqueness

- Product features and product performance,

- Complementary services,

- Intensity of marketing activities,

- Technology embodied in design and manufacture,

- Quality of purchased inputs,

- Procedure that influences the customer experience,

- Skill and experience of employees,

- Location (such as with retail stores),

- Degree of vertical integration (ability to control inputs and intermediate processes).

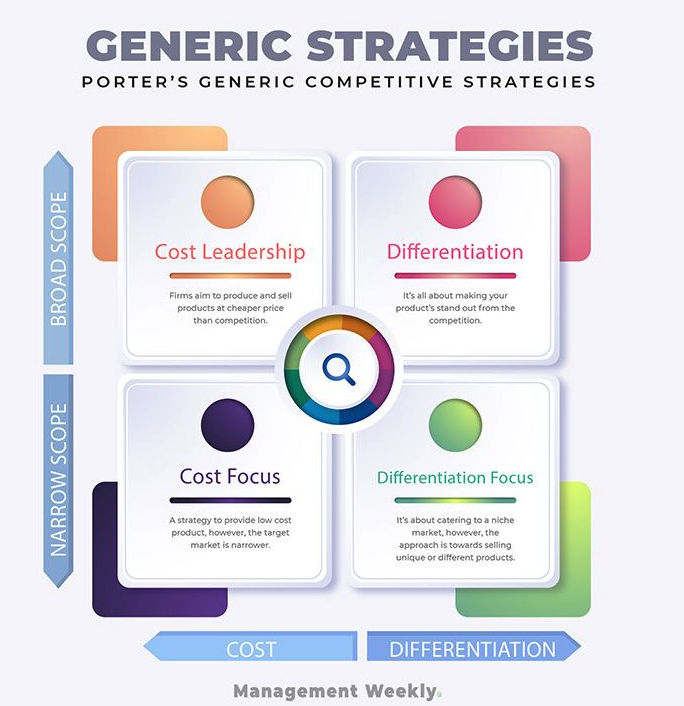

Porter’s generic (business) strategies

Michael Porter has also developed a complementary framework in 1980 to the one already developed for the industry profitability. The Porter’s Generic Strategies Framework has into account the two main generic strategies mentioned above. This framework is useful after selecting a given industry to operate and because it is not enough to be present in a market but a company needs also to be profitable. This is achieved by obtaining a dominant competitive position in the market following one of the three strategies: differentiation, cost leadership or focus. Failing to choose among the available strategies will endanger the company performance which will be stuck in the middle with strategic mediocrity and below-average performance. As explored in Business-to-You.com, the generic strategies are the following:

Differentiation

It is a type of competitive strategy with which a company seeks to distinguish its products or services from that of competitors: the goal is to be unique. A company may use creative advertising, distinctive product features, higher quality, better performance, exceptional service or new technology to achieve a product being perceived as unique. A differentiation strategy can reduce rivalry with competitors if buyers are loyal to a company’s brand. Companies with a differentiation strategy therefore rely largely on customer loyalty. Because of the uniqueness, companies with this type of strategy usually price their products higher than competitors. Examples of companies with differentiated products and services are: Apple, Harley-Davidson, Nespresso, LEGO, Nike and Starbucks.

Cost leadership

It is a type of competitive strategy with which a company aggressively seeks efficient large-scale production facilities, cuts costs, uses economies of scale, gains production experience and employs tight cost controls to be more efficient in the production of products or the offering of services than competitors: the goal is to be the low-cost producer in the industry. A low-cost position also means that a company can undercut competitors’ prices through for example penetration pricing and can still offer comparable quality against reasonable profits. Low-cost producers typically sell standard no-frills products or services. Examples of companies with cost leadership positions are: Southwest Airlines, Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, EasyJet, Costco and Amazon.

Focus

It is a type of competitive strategy that emphasizes concentration on a specific regional market or buyer group: a niche. The company will either use a differentiation or cost leadership strategy, but only for a narrow target market rather than offering it industry-wide. The company first selects a segment or group of segments in an industry and then tailors its strategy to serve those segments best to the exclusion of others. Like mentioned, the focus strategy has two variants: Differentiation Focus and Cost Focus. These two strategies differ only from Differentiation and Cost Leadership in terms of their competitive scope. Examples of companies with a differentiation focus strategy are: Rolls Royce, Omega, Prada and Razer. Examples of companies with a cost focus strategy are: Claire’s, Home Depot and Smart.

Stuck in the middle

A company that tries to engage in each generic strategy but fails to achieve any of them, is considered ‘stuck in the middle’. Such a company has no competitive advantage regardless of the industry it is in. As a matter of fact, such a company will compete at a disadvantage because the ‘cost leader’, the ‘differentiators’ and the ‘focusers’ in the industry will be better positioned to compete. It may be the case, however, that a company that is stuck in the middle still earns interesting profits simply because it is operating in a highly attractive industry or because its competitors are stuck in the middle as well. If one of the two exceptions are not present it will be very hard for companies to engage in both differentiation and cost leadership, Porter argues, because differentiation is usually costly. Each generic strategy is a fundamentally different approach to creating and sustaining superior performance and requires a different operating model.

Porter assumes that a company which tries to pursue both strategies of cost leadership and differentiation will be stuck in the middle. However, many authors have argued against this argument as Miller, 1992 who provides the example of Caterpillar company. The company brought a completely differentiated product to the market but forgot the economic and efficiency side. This allowed the Japanese competitors to enter the market. Furthermore, McDonald’s is an example of a company which, at the time of its foundation (it is arguable that the company still has a differentiated product), had a differentiated product but competed for lower prices as well as Southwest Airlines which is a low cost airline company but with a differentiated brand image. In addition, the blue ocean strategy that we analyzed in the beginning, suggests that a company can create a differentiated product in an unexplored market and still pursue low prices. Therefore, it is assumed that a company can pursue a combination of the strategies and still be successful.

Customer Intimacy and Other Value Disciplines

The question of why some companies thrive and overcome competitors in the market is common throughout this manual. The idea that companies succeed by selling value is not new. What is new is how customers define value in many markets. In the past, customers judged the value of a product or service on the basis of some combination of quality and price. Today’s customers, by contrast, have an expanded concept of value that includes convenience of purchase, after-sale service, dependability, and so on. Companies that have taken leadership positions in their industries in the last decade typically have done so by narrowing their business focus, not broadening it. They have focused on delivering superior customer value in line with one of three value disciplines—operational excellence, customer intimacy, or product leadership. They have become champions in one of these disciplines while meeting industry standards in the other two (Treacy & Wiersema, 1993).

The authors Treacy & Wiersema, 1993, developed a model trying to explain why some companies outperform the competitors by excelling in one of three categories and keeping market standards in the other two. This model particularly adds the concept of client focus by saying that a company capable of having high standards in costumer intimacy will have a better market position in relation to its competitors. This model is in line with Porter’s generic strategies as it also states the importance of the focus on a given segment. In this case, the authors suggest that instead of cost leadership or differentiation, companies should focus on what the clients value the most. As different clients value different aspects, companies should focus in one of them and keep standards in the other two. This model is based on value for the costumer.

The model provides the idea that the business strategies are not selected by the company itself but are perceived by the external environment (e.g.:clients, competitors). The company selects where it most creates value for the client (i.e.: product innovation, costumer intimacy or operational excellence) having in mind its internal resources and capabilities. Then, the external environment perceives the company in a given way, for example, as having a differentiated product or leading by costs.

Operational Excellence

The term “operational excellence” describes a specific strategic approach to the production and delivery of products and services. The objective of a company following this strategy is to lead its industry in price and convenience. Companies pursuing operational excellence are indefatigable in seeking ways to minimize overhead costs, to eliminate intermediate production steps, to reduce transaction and other “friction” costs, and to optimize business processes across functional and organizational boundaries. They focus on delivering their products or services to customers at competitive prices and with minimal inconvenience. Because they build their entire businesses around these goals, these organizations do not look or operate like other companies pursuing other value disciplines.

An example of operational excellence might be Walmart, the largest American retailer, which can assure low prices due to its supply chain, logistics and operations.

Customer Intimacy

While companies pursuing operational excellence concentrate on making their operations lean and efficient, those pursuing a strategy of customer intimacy continually tailor and shape products and services to fit an increasingly fine definition of the customer. This can be expensive, but customer-intimate companies are willing to spend now to build customer loyalty for the long term. They typically look at the customer’s lifetime value to the company, not the value of any single transaction. This is why employees in these companies will do almost anything with little regard for initial cost to make sure that each customer gets exactly what he or she really wants.

An example of costumer intimacy might be banks which keep a strong relation with their clients built on trust. Furthermore, Ritz-Carlton, the brand of a chain of luxury hotels, is a powerful example of tailored solutions and relation with the client.

Product Leadership

Companies that pursue the third discipline, product leadership, strive to produce a continuous stream of state-of-the-art products and services. Reaching that goal requires them to challenge themselves in three ways. First, they must be creative. More than anything else, being creative means recognizing and embracing ideas that usually originate outside the company. Second, such innovative companies must commercialize their ideas quickly. To do so, all their business and management processes have to be engineered for speed. Third and most important, product leaders must relentlessly pursue new solutions to the problems that their own latest product or service has just solved. If anyone is going to render their technology obsolete, they prefer to do it themselves. Product leaders do not stop for self-congratulation; they are too busy raising the bar.

An example of costumer product leadership might be a technological company offering cutting-hedge products or services. Samsung is an example of innovation for a long time.

Sustaining the Lead

Becoming an industry leader requires a company to choose a value discipline that takes into account its capabilities and culture as well as competitors’ strengths. But the greater challenge is to sustain that focus, to drive that strategy relentlessly through the organization, to develop the internal consistency, and to confront radical change. Many companies fail because they lose sight of their value discipline. Reacting to marketplace and competitive pressures, they pursue initiatives that have merit on their own but are inconsistent with the company’s value discipline. These companies often appear to be aggressively responding to change. In reality, however, they are diverting energy and resources away from advancing their operating model.

Corporate strategies

As we have seen in the beginning of this book, corporate strategy operates at a different level than business strategy.

“Corporate strategy is concerned with where a firm competes; business strategy is concerned with how a firm competes within a particular area of business”.

Grant, 2018

Although corporate strategy should always be coordinated with the business strategy, corporate strategy assumes a crucial role when a company, business unit or product line is not able to grow further (i.e.: it achieved maturity and is in decline).

When the product life cycle (it applies to business units, companies or industries) achieves its maturity and the product is not extended (i.e.:the product can be extended by introducing new features, reducing prices, advertisement), it will likely decline and reduce revenues. At this point, corporate strategies play a crucial role. It is not necessary to get to a decline point in order to exist corporate strategy. However, at this point a new strategy is required and the company could pursue a strategy of: vertical integration, outsourcing, diversification, alliances or internationalization. For instance, the Portuguese company Sonae decided to mainly pursue a strategy of diversification and currently operates in different industries. On the contrary, Jerónimo Martins has decided to go international and currently operates in several geographic locations. We will analyze each strategy and our analysis will be based on Grant, 2018 unless stated otherwise.

Little sidenote

To illustrate the product life cycle, we have used the BCG’s (Boston Consulting Group) matrix terminology. Just as a quick reminder the symbols mean the following:

- Stars: companies or business units operating in a market with high growth rate and with a large share of the market (possibly the largest operator in a given market). Very successful companies should have some business units in this section.

- Question marks: is the position in which new ventures or start-ups are in. They operate in a market with high growth rates but with low market share.

- Cash cows: after some time operating in a market, the growth rate declines but the company still has a large market share. This business unit provides consistent revenues but will likely stagnate.

- Dogs: it is likely that a business unit lose market share and if it operates for a long time in the same market, its growth rate will also decline. The revenue is very low.

Vertical integration and outsourcing

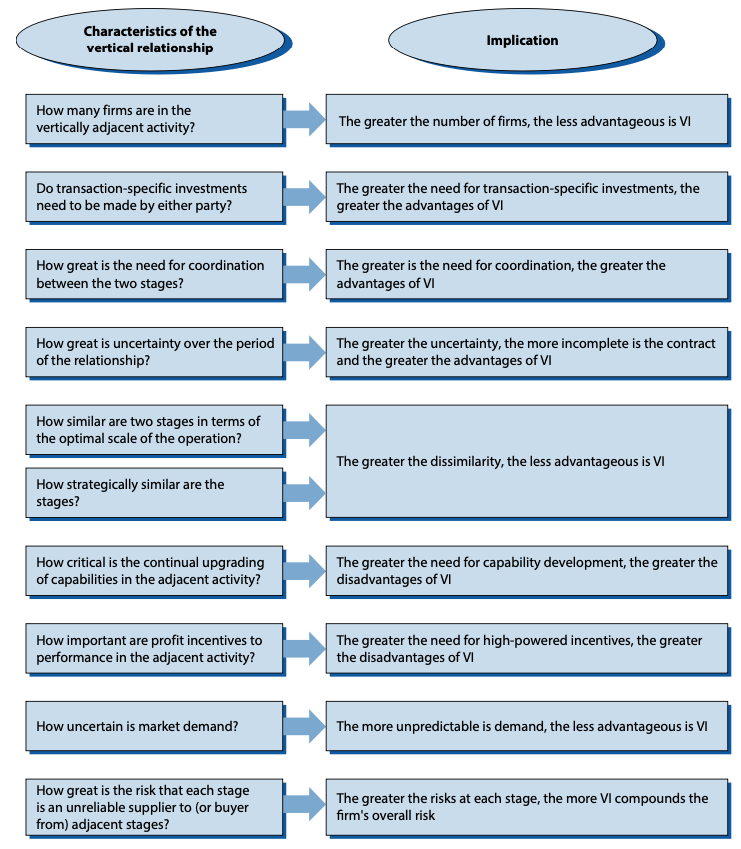

The scope of a company is the area in which it operates, in other words, it is the role it plays in the industry. For example, if a company only produces batteries, it has a much smaller scope than a company that produces batteries, car components and assembles electric vehicles. This role or scope can be defined based on the relative costs of performing a certain activity within the firm or delegate it to another firm (i.e.: outsourcing). The transaction costs concern delegating the activity to another firm and include costs of search, negotiation, signing contracts, monitoring and possible litigation. The administrative costs are the costs of perform an activity internally (i.e: internalize). Therefore, if administrative costs are lower than transaction costs, the company should perform an activity by itself. Scopes can be vertical, by product or geographical.

We will be focusing on the vertical integration strategy. Vertical integration is the firm’s ownership or control of several stages in the supply of a product vertically. In other words, how much of the process of producing a product the company owns by itself. Vertical integration can be backward (i.e.: suppliers activities as exploring lithium or producing batteries) or forward (i.e.: costumers’ activities such as selling and marketing a product). The strategy of integrating several activities into the firm is opposed to the strategy of outsourcing. The latter strategy concerns contract another firm to perform part of the production process avoiding higher costs for the company which does not have a capability of producing as good and cheap as the sub-contractor. Outsourcing can be beneficial when there is a collaborative relation between companies and can increase flexibility as the company will focus only on the activities it performs the best.

An example of a partially vertically integrated industry is the steel industry. Part of the activities are vertically integrated but other are not. For example, the steel production is not responsible for iron mining and has to negotiate a contract. Usually, there is only one single buyer and the profitability of the mining is dependent on the equilibrium of the bargaining power.

Benefits of vertical integration

- Cost savings: vertical integration can save costs for a company due to technical economies, in other words, joining different processes in the same location. For instance, it will be cheaper if a company produces batteries in the same location where it assembles electric vehicles.

- Avoids transaction costs: when a company has to deal with several partners in the production process, this action has transaction costs. If the process is entirely integrated, these costs disappear.

- Coordination benefits: a non integrated company needs to be completely coordinated with its partners. This coordination can be complex and time consuming if the product is highly specialized such as micro chips.

Costs of vertical integration

- Specialization: some companies are specialized in producing a given product and they do it well with low costs. If a company integrates certain processes it would incur in much costs with low chances of success. For example, a distribution company should not produce its own trucks or airlines should not produce their own airplanes.

- Distinctive capabilities: in line with the previous point, a company would need to have particular capabilities (i.e.: how it is done) to perform an activity. These capabilities are usually independent from activity to activity (i.e.: it is not the same to built trucks or to drive them). However, if these activities are similar to other that the company already has, vertical integration might be a good solution.

- Managing different businesses: the more a company vertically integrates, the more distinct the activities will be. It is a challenge to manage them all correctly as they belong to different businesses.

- Market incentives: when the activities are integrated the incentives to perform efficiently and diligently the tasks, disappear. This happens because the activities belong to the same company and the incentive to perform better is no longer there when the business will not profit from it (i.e.: there is a market competition to offer the best service which is no longer the case in vertically integrated businesses).

- Competition: when a company integrates certain activities becomes a competitor for what were previous partners. This will decrease the potential for partnerships.

- Flexibility and risk: flexibility is the rapid response to uncertain demand. When a company owns the entire supply chain it becomes less flexible to changes because it cannot simply divest from a certain activity or adjust to demand by simply adjust supplier contracts. The company will also be more exposed to risk as a problem at one step of the production process will affect others. It is a problem of the company when it integrates all the activities.

- Investing in unattractive businesses: companies which vertically integrate will probably invest in low revenue businesses which are unattractive.

Types of vertical relationships

Vertical relationships can assume three main types:

- Long-term contracts: the company can use spot contracts (i.e.: a good or service bought only once) or long-term contracts where the company is committed to a contract for a long period of time.

- Vertical partnerships: the company creates a long lasting partnership with backwards or forwards in the supply chain.

- Franchising: a contract is created between the owner of a brand and the franchisee which allows the latter to produce and market the franchiser’s product or service in a specified area.

Example: Tesla

Tesla is an example of a vertically integrated company which produces the batteries, the car pieces and assembles it. We can also see that Panasonic, which provides battery cells, has a factory within the Tesla factory. This makes one company totally dependent on the other but creates potential to efficient production and profitable partnerships.

Internationalisation

The internationalization of a company happens via trade (supply products or services from one country to another) and direct investment (building or acquiring assets in another country). The degree in which these two strategies are followed define the level of internationalization and the type of company. For example, if a company is only focused on the national market it is a sheltered company but if it performs both trade and investment in foreign countries, than it is a global company. These concepts are also applied generically to different industries. Companies pursue an international strategy not only to seek foreign markets but also to have access to a country’s capabilities.

The strategies of internationalization generally mean the access to another market with the potential to acquire new costumers and capabilities. On the other hand, it also means more competition which will be already located in the desired market. A company going international will potentially decrease the market share of incumbents and will face a response from them. The Porter’s five forces model can be applied in this situation to evaluate a market.

Comparative advantage

The term comparative advantage refers to the relative efficiency of producing different products. For example, the USA have high skilled workforce. Hence, they will have a comparative advantage producing technological products. On the other hand, Bangladesh has a low skilled workforce and has a comparative advantage producing labor intensive products, such as clothing. This comparative advantage can become a competitive advantage of a country or of a company investing in that country. When pursuing an internationalization strategy, companies should consider this factor.

Geographical location

The production of the firm depends deeply on the firm’s resources and capabilities are. If the resources are country-based it means they are only present in a given country. Therefore, the company should locate its production in that country. If the resources and capabilities are firm-based the company should locate its production where those resources are. The company should also consider if the resources are mobile (i.e.: if they can transfer them to other locations).

Apple produces its iPhone using suppliers worldwide probably using long-term contracts. The assembly is made in China but the microchips, the design and the software comes from the USA. Its cameras come from Japan and the sensors come form Germany and Italy. The company could also choose to pursue a direct investment in those countries acquiring a local company or building a company from scratch in order to have access to local market’s resources, capabilities and comparative advantage.

How to enter the market

When entering a new market a company can opt for two strategies: (1) transactions: less involvement and concerns exports and licencing; (2) direct investment: high degree of involvement in a market via joint ventures with local companies or own fully a local business.

The firm should take the following criteria into consideration before adopting an internationalization strategy:

- Competitive advantage based on firm-specific or country-specific resources: if the competitive advantage is based on the country where the company already operates then it should export. If it is firm-specific and the resources and capabilities can the transferable, the firm could pursue a direct investment strategy;

- Tradable product: if the product cannot be exported (i.e.: restrictions or physical aspects), then the company must invest in the foreign location;

- Resources and capabilities needed for success: the company must have the resources and capabilities needed to succeed in a foreign country. If it does not have them, it could pursue also a joint venture.

- Appropriate the returns: a company must be able to appropriate the returns of its investment. For example, a pharmaceutical company has a lot of legislation and patents protecting its products. Therefore, investing abroad might not be an option. However, it can appropriate the returns of local producers by providing licences to produce the medicine.

- Transaction costs: if a country imposes high tariffs and barriers for imports, a company may access this market easily through direct investment (i.e: China uses this technique to obtain direct investment).

Types of Foreign Direct Investment

There are two models of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI):

- Joint venture: it is an arrangement in which two or more companies agree to cooperate and join resources to accomplish a specific objective, usually, a new project or activity. The venture will be a different entity but the companies forming it are responsible for the profits and losses.

- Greenfield: in this case, the company creates a subsidiary company in another country from the ground up. This investment implies building an entire operation (e.g..: infrastructure).

There are three types of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI):

- Horizontal investment: the company acquires the same type of business operation in a foreign country (i.e.: internet provider buying a similar company in another country).

- Vertical investment: the company acquires a complementary business in another country (i.e.: a jewels manufacturer buys a mining business that supplies the company).

- Conglomerate investment: a company invests in a foreign business that is unrelated to its core business. As this could be very complex, this investment might be a joint venture.

Global strategy

A global strategy is the one that sees the world as single. Born-global companies are a type of company that from its inception seeks to compete in a global market and soon starts its internationalization process (typically technological companies). Companies pursuing a global strategy can obtain economies of scale and replicate a successful model elsewhere. These companies also gain access to global costumers and are not limited to national borders. This also allows the companies to explore local resources and capabilities and learn from the experience abroad from other companies. Once resources, capabilities and knowledge are acquired, companies are much more prepared to compete against other that are only focused in national markets (i.e.: experience and the possibility of using a large pool of resources).

Starbucks in Australia

Companies moving abroad must be aware of differences among markets. The desire to create a “global product” which is fit for every market is not always successful, mainly in businesses that deal with cultural specifics such as food. Companies must be ready to deal with cultural differences and be able to manage them either hiring or selling locally, for instance. Starbucks saw the Australian market as very attractive and decided to expand there with the same business model that it used in the USA. The company did not adapt the product even though Australians are not fans of american type coffee and have a strong culture regarding drinking coffee. As there was also no big recognition of the brand, the expansion was not successful.

Diversification

A diversification strategy is adopted when a company operates in different businesses, most of them unrelated (i.e.: J&J operates in the consumer business as well as in pharmaceuticals). This strategy is used in finance as a way of increasing portfolio value and decrease risk. Put simply, a diversified investor will the one having assets from different countries, industries or types. This will reduce the risk and increase value because if one business is not performing well, the investor is likely to not suffer hard consequences.

Similarly, diversified companies expect to obtain growth from different businesses and reduce risk because as they are diversified they are less exposed to shocks as an industry is under performing (i.e.: if the consumer business is under performing, J&J still has pharmaceuticals to balance). Particularly, if a company is pursuing growth and is in a cash cow or dog business (BCG matrix) it can diversify the areas in which it operates. The company ultimately seeks value creation for its stakeholders.

Value creation

Michael Porter defined three tests to assess if a diversification strategy will create value:

- The attractiveness test: the industries chosen for diversify must be attractive or capable of becoming attractive. Entering a new industry implies several challenges and to make these challenges worth, the industry must be attractive.

- The cost-of-entry test: the company must consider the costs of entering an industry. For example, the pharmaceutical industry remains so profitable because of high entry barriers. An entry in such an industry is more likely to succeed through acquisition.

- The better-off test: this test deals with synergies. When entering a new industry what is the potential for interactions between the two businesses that can enhance the competitive advantage of either business? If there are no synergies at all, maybe diversify is not the best option.

Economies of scope

The primary source of diversification comes from the better-off test. It concerns the exploitation of linkages between businesses. “Economies of scope exist when using a resource across multiple activities uses less of that resource than when the activities are carried out independently” (Grant, 2018). This concept is linked to synergies (i.e.: two activities together perform better than in separate).

- Tangible resources: can be shared among diversified industries if different businesses can use them. For example, TV companies diversify into the telephone or music stream businesses to share costs of networks maintenance and share costumer databases or costumer centers. When calling to a TV operator we can contract a streaming platform, internet and telephone.

- Intangible resources: intangible resources such as brand recognition or technology can be easily used by several businesses at a low cost. Starbucks has expanded its brand to coffee, ice cream, coffee machines or books.

- Organizational capabilities: can also be transferred to several businesses. For example, Apple used its capabilities of expertise, design or engineering to create different products such as smartphones, computers, TV boxes or tablets.

The firm as an internal market

An economy is composed by different actors. In summary, there are two relevant markets within an economy: (1) capital market and (2) labor market. A diversified company has both these markets due to its size.

- Capital market: a diversified company has several sources of revenues which can be invested in different businesses. For example, if a business produces long streams of revenues, it can finance other business without using external financing such as loans or bonds. This process can cause internal competition for funds and must be well managed.

- Labor market: a diversified company can transfer employees along several businesses, particularly, managers and technical staff. This reduces the need to hiring and firing which also reduces costs. This can benefit employees as they will have enhanced career opportunities but also companies which have a pool of resources internally available. Nowadays, companies use policies of internal mobility to take advantage of this internal labor market.

Relatedness

The concept of relatedness in diversification concerns the expansion into related businesses instead of completely unrelated ones. It was assumed by researchers that a diversification strategy into related industries would be more profitable as the resources and capabilities would be automatically transferable among businesses.However, there is no clear proof of that.

Indeed, studies have focused on the operational level of relatedness which concerns the resources and capabilities transfer. However, an important ability in a diversified company is to apply common general management capabilities, strategic management systems, and resource allocation processes to different businesses. This is more related with strategic than operational similarities. For example, Berkshire Hathaway (investment company founded by Warren Buffet), invests in completely different businesses without any relatedness. They all benefit from the management style of Berkshire Hathaway in the person of Warren Buffet.

Johnson & Johnson is splitting businesses

Johnson & Johnson is one of the most diversified companies worlwide. It operates mainly in the consumer business, medical devices and pharmaceuticals. Recently, the company has decided to split its consumer business from the other two due to lack of synergies among them.

Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) and strategic alliances

Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) and strategic alliances are other strategies that a company could pursue at a corporate level. These strategies are within the external growth strategies as they focus on the outside of a company by forming an alliance or by acquiring or merging with another company. These strategies are the main and fastest way for a company to increase its size and scope of activities.

- Acquisition: is the purchase of a company by another. This purchase requires an offer to the stock of the other company. Takeovers (i.e.: acquisitions) can be friendly or hostile if they are not supported by the board (or shareholders) of the other company.

- Merger: implies the merge of two companies to form another one. This requires the acceptance of the shareholders of both companies as they will need to substitute their shares by stock of a new formed company. Merges usually occur with companies of similar sizes.

- Alliance: is a collaborative arrangement between two or more firms to pursue agreed common goals. The most well-known are the airline alliances.

Motives for M&A

There is no consistent proof of the real advantages from following a M&A strategy. Several studies provide evidence of small increases in shareholder value as well as for the companies themselves. Nevertheless, there are successful M&A cases. M&A serves mostly to acquire resources and capabilities than a business itself. The motives to follow a M&S strategy can be the following:

- Managerial: M&A can be very appealing to top managers, in particular to CEOs. They tend to pursue this strategy as a personal quest for power (managerial and financial) and psychological satisfaction. The reason is that M&A provide the fastest route to corporate growth.

- Financial: M&A can generate shareholder value for financial reasons. First, the stock of the company can increase value after an M&A (due to perception) and automatically increases the value for shareholders. Second, M&A can prove to be useful dealing with taxes for example by acquiring a poorly performing business which will provide tax credits by reducing profit artificially. Third, M&A can be done using debt (i.e.: a company acquires stock of another company using bonds) which is cheaper than equity.

- Strategical: M&A have the potential to increase the profits of the firms involved via: (1) horizontal merges: combine firms that compete in the same market; (2) geographical mergers: acquire a firm in another geography and expand to different markets; (3) vertical merges: acquire a supplier or a client and own the entire supply chain; (4) diversifying merges: acquire a company operating in a different business. M&A is the main source of diversification.

Forms of alliances

Strategic alliances may take different forms:

- Equity: an alliance may or may not include equity participation. Most alliances are agreements and do not involve ownership links.

- Joint venture: equity alliance where a new company is formed and the partners take equity part on it.

- Purposes: alliances may be created for a wide variety of purposes from creating a car component to provide costumers the widest rage of coverage in air travel.

- Relationship: alliances can be bilateral or multilateral. The latter form is a network of companies which work together. Most of the companies assembling complex products opt for this form.

Motives for alliances

The motives to pursue alliances are the following:

- Complementarities: exploit complementarities between resources and capabilities of both firms. For example, Uber and Volvo Cars established a project to develop fully-autonomous cars.

- Learning: a company may form an alliance to learn capabilities from another company. For example, South China Locomotive & Rolling Stock Corp.’s alliances with Bombadier and Siemens were motivated primarily by the desire to acquire their technology.

- Flexibility: alliances can be created and dissolved easily and do no involve such enormous costs as M&A.

- Risk sharing: companies share the risk of doing business and investment. For example, most of the discovery projects of oil are done via alliances due to the enormous costs involved.

Framework to evaluate the best strategy

The following framework proposes an example to analyse which strategy to take: acquisition or alliance.

Environment characteristics:

- Strategic uncertainty: uncertainty of the external environment;

- Dispersion of knowledge: the knowledge to develop a new business is dispersed;

- Urgency: urgency for additional resources and capabilities;

- Competition: competition in the market.

Transaction characteristics:

- Specificity: costs related with the establishment of the alliance;

- Opportunistic behavior: behavior of the partner company;

- Strategic intents: alignment of the strategies of partner companies in an alliance;

- Expected duration of the synergies: if synergies are expected to be long term, it favors acquisition.

Company characteristics:

- Resource endowment: level of internal resources needed for acquisition (i.e.: financial or capabilities);

- Management capabilities: mainly related with the capabilities and experience of the managerial team;

- Absorptive capacity: ability to learn and adapt. If a company is able to learn and adapt faster than the partner, alliances could provide a good option but opportunistic behavior of the partner should not be disregarded;

- Appropriability regime: ability to protect company’s core capabilities and resources from unwanted appropriation by an alliance partner.

Airline alliances

Air alliances are probably the most well known form of alliance. They intend to provide clients with the widest coverage possible using the routes of the several companies composing the alliance. For instance, if Lufthansa cannot fly directly to San Francisco but only to New York, it will leverage on the routes of their American partners to offer the client that trip.

Resources and References

Main

- Barney, J. & Hesterley S. (2019). Strategic Management and Competitive Advantage: Concepts and Cases. 6th Edition, Pearson.

- Grant, R. (2018). Contemporary Strategy Analysis. 10th Edition. Wiley.

Secondary

- Adam Brandenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff, Co-opetition (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1996)

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management.

- Bredrup, H. (1995). Competitiveness and Competitive Advantage. In: Rolstadås, A. (eds) Performance Management. Springer, Dordrecht.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1212-3_3

- Boddy, D. (2020). Management: Using Practice and Theory to Develop Skill (8 ed.). Reino Unido: Pearson.

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Sage. (direct link)

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: taking another look. Int J Corporate Soc Responsibility 1, 3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6

- Casadesus-Masanell, R. (2014). Introduction to Strategy. Harvards Business Publishing

- Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T., & Eisner, A. B. (2010). Strategic management: Text and cases. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Lacaze, A., & Ferreira, F. (2020). Adding Value to the VRIO Framework using DEMATEL. Lisbon: ISCTE-IUL. (direct link)

- Levitt, T. (1958). The dangers of social responsibility (pp. 41–50). Harvard business review

- Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2004). Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business Review. (direct link)

- Miller, D. (1992), “The Generic Strategy Trap”, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 37-41.https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039467

- Nagel, C. (2016). Behavioural strategy and deep foundations of dynamic capabilities – Using psychodynamic concepts to better deal with uncertainty and paradoxical choices in strategic management. Global Economics and Management Review, 44-64. (direct link)

- Pearce, J. and Robinson, R. (2009), Strategic Management – Formulation, Implementation and Control, 11th edition, McGraw-hill International Editions

- Porter, M. E. (1979). How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harvard Business Review. (direct link)

- Porter, M. E. (1985). The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. NY: Free Press

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press.

- Porter, M.E., & Kramer, M.R. (2011) ‘Creating shared value’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 89, no. 1/2, pp. 62–77.

- Sharda, R., Delen, D., & Turban, E. (2018). BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE, ANALYTICS, AND DATA SCIENCE: A Managerial Perspective. Pearson.

- Teece, D. J. (2011). Dynamic capabilities: A guide for managers. Ivey Business Journal. (direct link)

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1998). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal. (direct link)

- Treacy, M., & Wiersema, F. (1993). Customer Intimacy and Other Value Disciplines. Harvard Business Review. (direct link)

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). The Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal.

Websites

- https://ebrary.net/99185/business_finance/which_prioritie

- https://managementweekly.org/porters-generic-competitive-strategies/

- https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/bezos-is-coming-mapping-amazons-growing-reach

- https://www.business-to-you.com/ansoff-matrix-grow-business/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/levels-of-strategy-corporate-business-functional/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/porter-generic-strategies-differentiation-cost-leadership-focus/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/value-disciplines-customer-intimacy/

- https://www.business-to-you.com/vrio-from-firm-resources-to-competitive-advantage/

- https://businessjargons.com/internal-environment.html

- https://www.finereport.com/en/data-visualization/a-beginners-guide-to-business-dashboards.html

- https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/change-management-process

Pingback: Change management how to approach to solutions - nomadOso

Pingback: How to Pitch your Project: Do NOT sell Ideas - nomadOso